I was asked by Peter Askim, the music director of Raleigh Civic Symphony Orchestra, to write a piece for his group. He said that the 25 minute work would have a virtual reality component built by graduate students of North Carolina College of Design, led by Derek Ham, on a theme of suffragettes.

In 2017 Peter gave the world premiere of my Echolocations in New York’s Le Poisson Rouge; we had divided a string orchestra into three groups to play an identical material, at different times, from three different locations in the hall.

The experience was magical, as if the sound were coming from all around the audience, echoing across space. Textures and volume mixed and merged right next to one’s ear as well as in the distance. There was a sense of oneness between the musicians/sound and the audience since the stage as a divide did not exist.

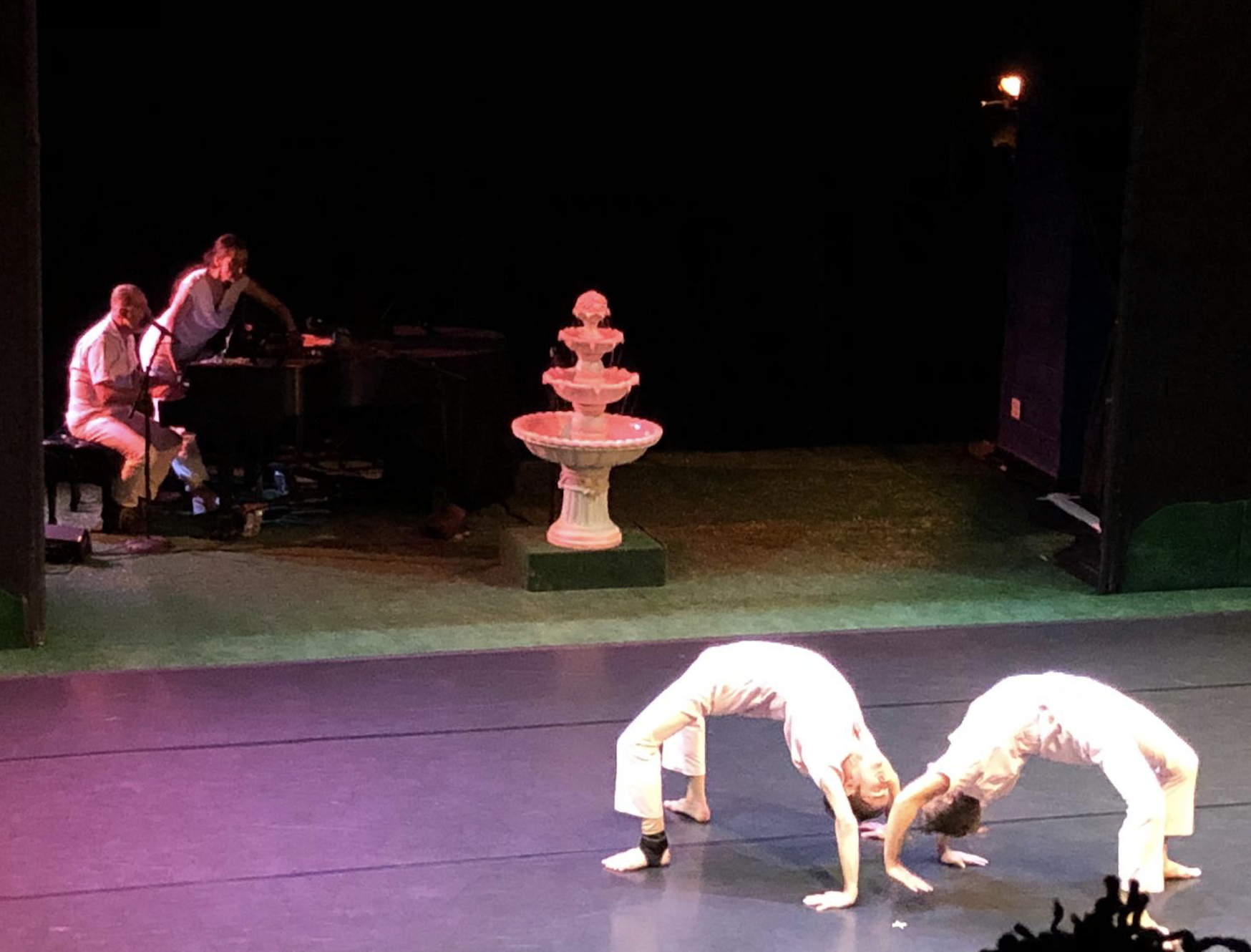

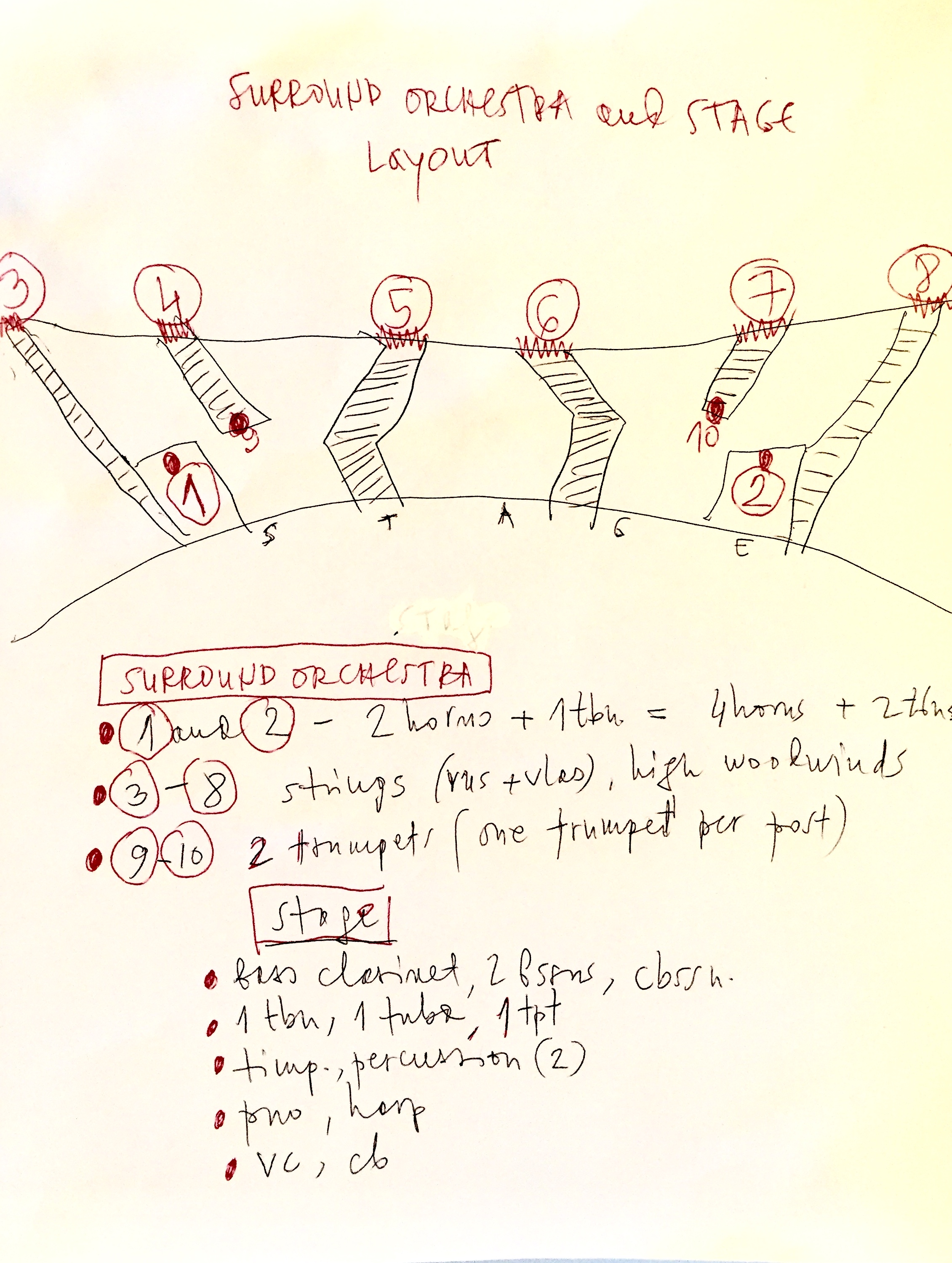

Peter asked me to do something similar with the new work – to spatialize the orchestra. It is a dream situation to get permission from a conductor (Peter is also a composer and a bass player) to break the standard layout of this gigantic body of sound and explore it. There were several things to solve: how to make musicians comfortable while away from their usual places on stage; how would they follow the conductor and be able to hear others if they are dispersed throughout the auditorium; would they like the idea of being challenged that way, since their experience is to belong to a group and play as a group; where would they stand in the specific hall that I never visited? I got photos of the hall – there was room to have musicians in different spots, so I decided to divide them into Surround and Stationary groups. Instruments that can’t move would stay on stage and be the Stationary orchestra, while the Surround orchestra with all portable instruments (high strings, woodwinds and high brass) would be positioned around the audience.

The piece needed to be lean in terms of notation, as the lighting, stands, and all elements of the orchestral setup would not apply to this performance. (Also, Surround orchestra members would be standing for the duration of the entire piece.)

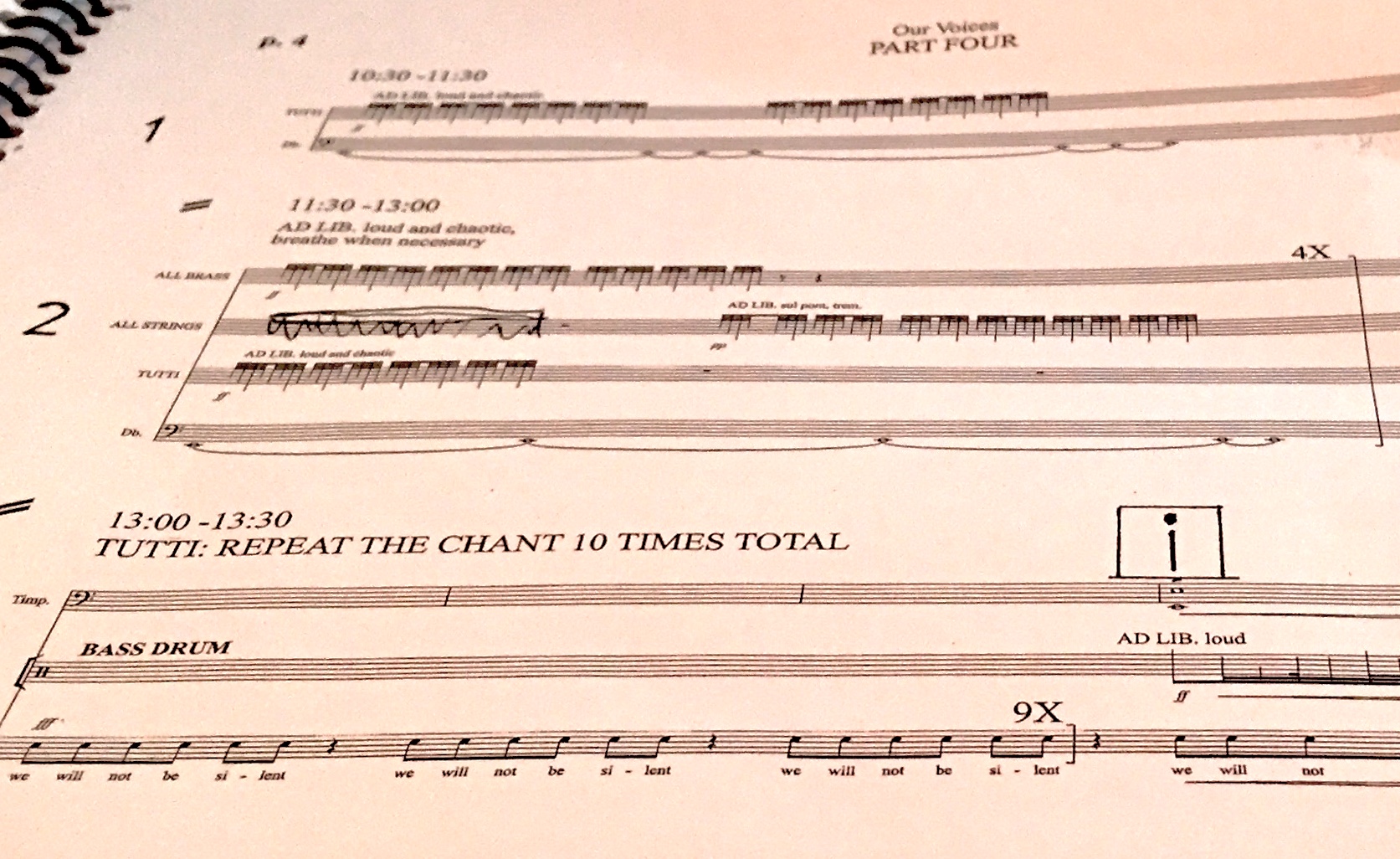

I divided the piece into six sections framed by Intro and Epilogue. In both Intro and Epilogue, musicians are asked to use their voices. In Intro, everyone gradually joins in a hum on A a cappella, while in the Epilogue the Surround orchestra members walk through the auditorium calling the names of women in their lives who inspired them: their grandmothers, mothers, sisters, wives, teachers…it’s a personal choice.

Parts 1-6 are all organized around pitch centers (B, C, D, E, F, and G) so all musicians can come in and out of playing, knowing how to fit in harmonically. The score is open, no meter, mostly aleatoric, with options offered, but choices entirely upon the 80 people playing the piece. The role of the conductor is to keep time and organize transitions, while his gestures do not mark sharp beginnings or endings of gestures and sound. Transitions between the sections are fluid and overlapping.

There were many interesting insights during our rehearsal in Raleigh, NC this week: most of musicians in the orchestra would start and stop immediately following conductor’s gesture although the instruction states – the conductor’s gesture means you can start from this point on at your own time; or with the ending – wrap up your material at your own pace and move onto the next thing.

The atmosphere during the one rehearsal I attended was inspiring – we were searching for new ways of individual expression, trying out new techniques not so common in the standard orchestra repertoire, understanding the concept of musical time in which there is no counting, but listening and responding instead, discovering ways to feel safe without the structure of barlines and meter.

In terms of rehearsal methodology, Peter had me talk to the orchestra about each section, then we played it through, worked on timing and explored sound, and played it through again. After going through the entire piece we were ready to try spatialization. The Surround orchestra members placed themselves around the rehearsal space, all of them behind the conductor – and we had the first run-through. The sound was traveling in all directions creating most beautiful, unexpected sonorities.

My favorite part was when the orchestra for a brief moment accompanied the recording of Billie Holiday singing Strange Fruit. Again, there was no meter, barlines – just Billie’s voice with her beautiful, free, out-of-time phrasing.

Peter and I had several conversations on how to make that segment with Billie Holiday doable for the orchestra. I didn’t want to transcribe the song with any specific metric or tonal changes. My idea was to have the orchestra follow her voice, rather than following the conductor. The very topic of the piece – the struggle for equality, somehow symbolically came up in the treatment of that sample from Strange Fruit: in an ideal world of citizens with high consciousness we would not need to be told what to do and whether and when to support the voice of another. By listening and doing our best to understand and support the other we would create a different humanity.

Peter’s concern for precision and clarity was a great reminder that I am creating a work for eighty people whose comfort and success in delivering that music also depend on how aligned they feel with one another and the recording of Billie’s voice. We were deliberating whether I should rewrite the score and instead of just saying ‘follow Billie, c-minor” write out orchestral parts transcribing the metric freedoms that she takes while singing. I decided against it. In this specific case I wanted each individual to take charge, be responsible for their choices, listen, try to provide support, swim in uncertainty if so happens, rather than follow the conductor. The invitation to the orchestra to join in freely around Billie Holiday’s voice in Our Voices calls for a personal, unique contribution of everyone involved in the piece, rather than an orchestrated, controlled response. The thinking through of those two options (lock it in a standard notation or keep it as open as possible) inspired me to write a poem about how I made musical choices in this piece. The poem also reflects on a larger context of what it means to belong to and to create our humanity. I dedicated the poem to Peter, who invited me and trusted me throughout this creative adventure.

Accompanying Billie Holiday in Strange Fruit

Do

Not

Be

***

At

Me

I am like you

And you are like me

Doing my best

Often fast

Sometimes slow

Wanting all

And then some more

Creating order

Bliss or mess

Still true and real

Despite distress

Those Billie-lines

More than once

Made me cry

As I fit them

In odd times

Whole notes

Half notes

Aren’t wrong

They are

Dark and lost

To song

Of pain and

Crisscrossed time

No chance to

Truly align

Unless

We all agree

That

What is yours

Is also mine

What was theirs

Was hers at times

Wanting best

Yet often failing

Feeling rough

Still trust prevailing

Contrasts of

Wants and coulds

Of possibles and shoulds

No wiser thing

No greater power

Than seeing

With one’s heart

Into the dark hour

Of those Billie-lines

They might also

Make you cry

As you play them

In odd times

London, January 29, 2019, for my friend, collaborator, and a fellow composer Peter Askim.

Our voices was commissioned by NC State University and NC State Sustainability Fund. Our Voices has been featured on NCSU Website: